The Paradox of Security

"The Most Secure Control System is the One that Doesn't Exist."

Many of you who have known me for decades know that my passion lays at the core of automation, control, and safety. Having lived in this world prior to cybersecurity concerns in the late 90s and early 2000s (Y2K) has given me a perspective that has brought me to author this article. This is my personal viewpoint - and as we walk in over the threshold of the rug at your shoreside facility gates or step off of the helipad into the safety briefing that typically proclaims, “Safety Starts Here”, we must realize that in today’s world maritime control systems connectivity has far exceeded your port or vessels’ perimeters. And so began the importance of and pursuit of securing maritime control and safety critical systems onshore and offshore.

In our pursuit for secure maritime digital control systems though, we often get caught up in the allure of sophistication. High-tech firewalls and encryption algorithms give us a sense of invincibility. But at the heart of it all, there is this fundamental need for trust relations.

Trust is at the core of any maritime digital control system. Operators trust the sensors, engineers trust the algorithms, and offshore installation managers trust the overall integrity of the control, and, most importantly, their safety critical systems. It is this intricate web of trust that keeps everything running smoothly. Yet, this reliance on trust can be a double-edged sword.

A fully digital bridge, linked to digital control, safety-critical systems, and remote access.

A fully digital bridge, linked to digital control, safety-critical systems, and remote access.

After many years, well ...actually over a decade in my mind’s eye, I have been working out some of the concepts that I have witnessed along the way. We started many decades ago to get to where we are today in terms of systems, architectures, and the people and culture aspects bound to advancements in technology. This led me to compile and present on the topic of Normalization of Deviance. I was fortunate enough to have been able to bring this talk to the OTCEP in Singapore in 2023, and this year at the S4x24 conference in Miami. (YouTube: Link to the talk here.)

A ship system using digital automation and safety.

A ship system using digital automation and safety.

The big idea is that gradual acceptance of deviations as normal behavior. In the context of safety-critical systems including maritime digital control, we may be allowing unverified trust to seep into the system. As port facilities, offshore installations, and their supply chains expand beyond physical boundaries, the trust network follows suit. The perimeter extends far beyond the port of offshore facility, connecting with external entities into a complex digital ocean.

The assumption is that these external components are as secure as the internal ones. And that is where the challenge lies, folks. Unverified trust beyond the traditional boundaries introduces vulnerabilities. If we are not careful, a breach in any part of this extended trust network can have severe consequences, affecting the entire manufacturing process, safety of the site crew, and extending beyond the facility perimeter to include public safety and the potential for environmental impacts.

It is a delicate balance. I have shared the following thought with co-workers and the students I have trained: "The most secure maritime digital control system is the one that doesn't exist". It is intriguing. Paradoxical. While complete nonexistence is perhaps unattainable, it prompts us to reevaluate our security strategies. So, how do we navigate this web of trust without compromising the integrity of the entire system?

"It Depends" is the most common answer you will receive, and that requires a comprehensive approach.

Let us delve a bit deeper into the safety-critical system implications of safety. The normalization of deviance in trust relations can have profound effects on safety measures. When we extend our trust unchecked, we might overlook potential hazards or deviations that could compromise the safety protocols designed to protect not only the process but also the people involved. Blatantly put, this extended trust could potentially lead to a situation where safety measures are compromised.

Consider a scenario where external components integrated into our trust network do not adhere to the same safety standards. If we normalize this deviance, assuming everything is in order, we might inadvertently compromise the safety measures we have put in place. It is a delicate balance between efficiency and maintaining the robustness of our safety protocols. Safety should always be at the forefront of our considerations. So, how do we approach and navigate this challenge, ensuring that our pursuit of trust and technological advancement does not compromise the safety measures critical to the integrity of the entire system?

Elements that are often discussed after deployment and that need to be part of your discussions at conceptual design are:

- The Illusion of Sophistication

- Trust and Normalization of Deviance

- Expanding the Perimeter

- Challenges of Unverified Trust

- The Nonexistent Ideal

- Just Because You can Doesn't Mean You Should

The assertion that the most secure maritime digital control system is the one that doesn't exist is a provocative contemplation. It challenges us to reconsider the very nature of security in an interconnected world. While complete nonexistence may be an unattainable ideal, acknowledging the inherent vulnerabilities of trust relations prompts a reevaluation of security strategies.

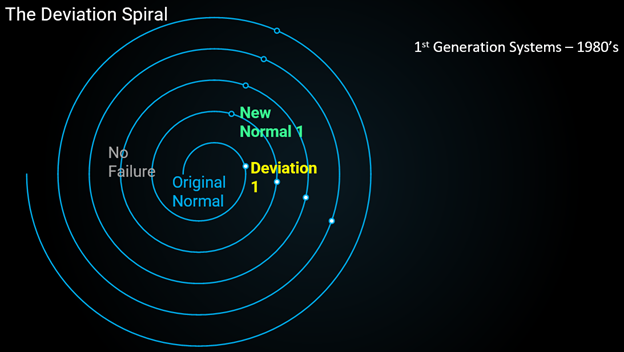

Image 1 Spiral: 1980s companies began the move to logic controllers along this SPIRAK, speaking to the deviation and the new normal.

Image 1 Spiral: 1980s companies began the move to logic controllers along this SPIRAK, speaking to the deviation and the new normal.

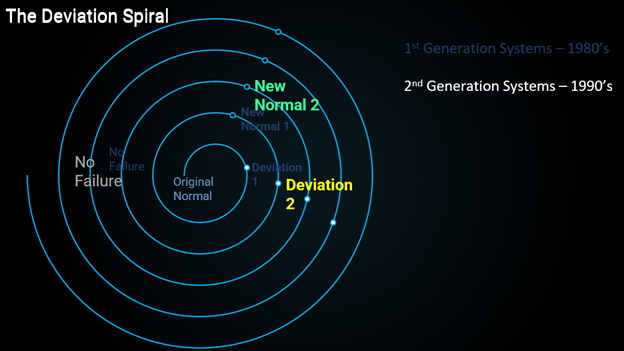

Image 2 Spiral: Late 1990s companies began integrating process historian from their control systems at sites to enterprise with minimal security thought.

Image 2 Spiral: Late 1990s companies began integrating process historian from their control systems at sites to enterprise with minimal security thought.

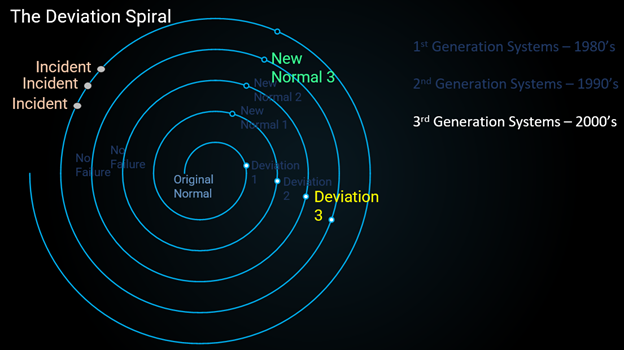

Image 3 Spiral: 2010 Virtualization in Control Systems become proven, and vendors begin to allow integration, new adoption of cloud for SCADA.

Image 3 Spiral: 2010 Virtualization in Control Systems become proven, and vendors begin to allow integration, new adoption of cloud for SCADA.

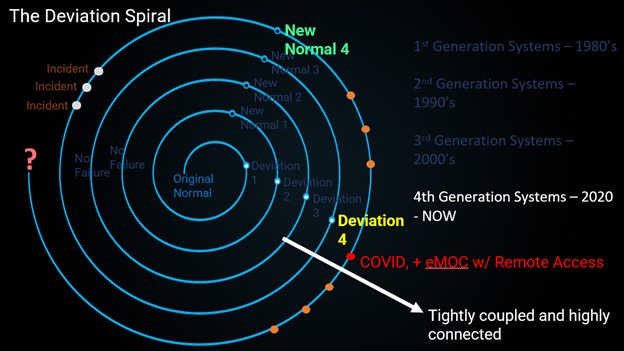

Image 4 Spiral: 2012 to today with lloT and ICSS along with supporting standards allowing system to able fully integrated and supported remotely through intranet/public internet.

Image 4 Spiral: 2012 to today with lloT and ICSS along with supporting standards allowing system to able fully integrated and supported remotely through intranet/public internet.

Wrapping this Up

In the pursuit of a secure maritime digital control system, it is imperative to recognize the paradox of security – that even the most sophisticated systems are built on a foundation of trust. Normalization of deviance and the extension of trust beyond the traditional boundaries of manufacturing sites demand a comprehensive approach to security. While the complete nonexistence of a system may be a utopian concept, understanding the intricacies of trust relations is crucial for fortifying the defenses of our interconnected industrial landscape. It is about finding that sweet spot between technological advancement and the inherent complexities of trust relations.

In maritime digital control systems, it is not just about technology; it is about a nuanced understanding of human behavior and the dynamics of trust. As we move forward, let us ensure that our pursuit of sophistication does not blind us to the vulnerabilities that lie within the very fabric of our interconnected systems, especially when it comes to ensuring the safety of our processes and the people involved.

To learn more about unverified trust, assessment method, and measures to address the risks, visit the INL website: Idaho National Laboratory CCE | Idoho National Labortory CIE.

Many thanks to the great work of Dr. Diane Vaughan regarding normalization of deviance. I would also like to thank Adam Starr for his deviation spiral inspiration and input for my talk.

About the Author

Marco Ayala

Houston InfraGard Members Alliance

marco.ayala@infragardhouston.org

Marco Ayala has over 28 years of experience where he designed, implemented, and maintained process instrumentation, automation systems, safety systems, and maritime vessel control networks. With two decades focused specifically on industrial cybersecurity, he has led efforts to secure the oil and gas (all streams), maritime port, offshore facilities, and chemical sectors, supporting federal, local, and state entities for securing the private sector.